The 1913-14 season had been a bumper season for the Football League. Blackburn Rovers won the league at a gallop, 7 points clear of second place Aston Villa. Both the First and Second Division had enjoyed record aggregate gates and average attendances were up 17% on the 1912-13 season. The 1914 FA Cup final at The Crystal Palace between Burnley and Liverpool was considered a less glamourous affair than the cup final the year before between Aston Villa and Sunderland. The cup final attendance had fallen by 60% on the previous year, however the FA had gained one important spectator in King George V who gave away the trophy and medals. For the Football Association having the King as guest of honour was a signal that the professional game was starting to be accepted by the political and cultural elites.

All was set for an exciting 1914-15 season. A long hot summer was enjoyed by everyone and then a crown prince and his wife were murdered in a Balkan city.

Tuesday 4th August 1914, Great Britain declared war on the German Empire. On the 8th August the great retired cricketer Dr WG Grace wrote in The Sportsman that football should cancel their new season. He also said the current county cricket championship scheduled to end on the 2nd September should be abandoned. Apart from Surrey and Derbyshire Dr Grace’s plea was ignored.

The Football League Management Committee had a meeting on the 6th August, but they only mentioned the war in passing as although some football grounds were being used for mobilisation of army reserves, it was not thought that this would affect the opening league games.

The start of the Football League was to be its traditional first day of September. The 1st September fell on a Tuesday. Two First Division games and three Second Division were scheduled for that day and by the first Saturday nearly all clubs would have played two matches.

As August drew to a close and fighting in Europe intensified, the Football League decided they couldn’t cancel the oncoming season. They were in a helpless position as league clubs had to honour the 1,800 current player contracts and the Government had said that all legal business contracts should be honoured as usual. This was as it happens the same position the Northern Rugby League took, they too carried on with their new season, but they later brought in emergency rules for the rest of the war.

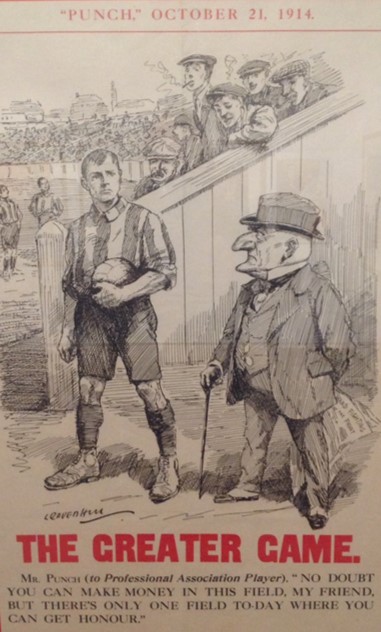

Rugby Union on the other hand, all but shut up shop. A circular from the RFU (Rugby Football Union) sent to all clubs saying they should cease playing and encourage their players to join the military. This was easy for rugby union to do as being an amateur sport they had no contracts to honour.

Frederick Nicholas Charrington, social reformer and temperance worker, had written to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph on the 4th September to say that the decision to carry on with the league was unpatriotic and filled British people with shame and indignation. He went on to write that football games should be used as an opportunity for a recruitment drive for the armed forces.

Charrington carried this through on the 5th September by turning up at the first match of the season at Craven Cottage where Fulham entertained Clapton Orient. It was agreed he would confine himself to advocating enlistment to the crowd at half time, however this quickly turned into a diatribe against the playing of football during war time. Fulham who were enjoying the largest gate of the day in the Second Division, did not enjoy Mr Charrington’s behaviour and he was unceremoniously ejected from the stadium.

On the 14th September the Football Association bent to public pressure by putting their football grounds at the disposal of the War Office as drill grounds on days other than match days. They also arranged to have well known public men address spectators and players in the interests of recruitment.

The opening week’s Football attendances were down by 50% and as the season rolled on football attendances had fallen by 63% on the previous season. With this fall in gates and revenue, the Football League set up a committee to help out struggling clubs with extra money to cover their commitments and wages. By October the Football League brought in a 2.5% levy on gross net receipts for the League’s relief fund, set up to aid clubs that found themselves in financial difficulty during the war.

Keeping the league programme going became increasingly difficult as the railway system creaked under the pressure of wartime demand. Occasionally away teams and match officials arrived late for matches, but on the whole the league muddled through.

Player wages came under pressure as the season progressed. The Football League responded by reducing the maximum player wage from £206 per year to £156. It had become apparent that whatever the future held for league football, there would be no summer wages for players. Most had already taken large pay cuts and for all the future was either service in the armed forces or long hours in a munitions factory, both of which paid less money.

The FA Cup got under way with the Extra Preliminary Round on the Saturday 12th September. The FA Cup suffered less criticism at this stage, as these early rounds only concerned non-league clubs and drew little national interest. As the competition unfolded and the war stepped up in intensity the FA responded by changing its rules.

In December 1915 with the first round proper about to start, the FA adopted a rule that from the second round onwards, if first games were equal after 90 minutes, extra time would be played. Replays would also go to extra time, and if after that the match was still tied, a 2nd replay would be played. Playing mid-week was out of the question as the FA decided that all cup games would be played on a Saturday to avoid disrupting the war effort. Replays could therefore result in postponing league matches. The first round of the FA Cup in January is traditionally the first to involve clubs from the Football League, and the first two rounds passed off without incident or need of a second replay.

It was a third round tie between Bradford City and Norwich City where the trouble started. The initial tie ended 1-1 at Bradford and the replay 0-0 at Norwich, both after extra time. Time was running out for the FA as the fourth round was scheduled for Saturday 6th March, and the first Norwich City v Bradford City replay had taken place the Saturday before. Without a Saturday to play the match on and football facing criticism in the press and Parliament, the FA decided to hold the 2nd replay at the neutral venue Sincil Bank, Lincoln on a Wednesday afternoon behind closed doors, so as to not distract men from their war work.

The FA decided that they would also need to extend the season by one week, so, if needed they could fit in a cup final replay. They also moved the final away from The Crystal Palace and London, for the first time in 20 years. The venue had yet to be chosen and though the Admiralty had taken over The Crystal Palace they said it was still available to the FA if they wanted it. The FA decided they might face criticism if they push the Admiralty out, even just for one day. They decided they would probably move the cup final north, though Stamford Bridge was still an option.

The next attack on professional football came from a letter dated 26th March from Colonel CF Grantham commanding officer of the 17th (Service) Battalion, the Duke of Cambridge’s Own Middlesex Regiment (Football), also known as the Footballers’ Battalion. Colonel Grantham pointed out that only 122 professional footballers from the Football League and Southern League had signed up to the armed forces whilst 1,800 players were still playing, citing this as a public scandal. He also claimed to have proof that many football managers and directors gave no assistance to their players to enlist, and actively prevented them from joining up.

Before the Football League and the FA could do anything to answer this they we hit with another letter from FN Charrington, writing to the Editor of the Manchester Courier. He opened his letter with a half-truth, ‘The Football Association having abandoned the idea of playing the Cup Final in the South, on the grounds that public opinion is too strongly against them’… The reason Old Trafford had finally been chosen as the venue for the final, was because Stamford Bridge was the only real option in the capital. Chelsea were still in the competition at that point, if they reached the final, FA rules stated that a club playing in the final could not host the final, an event that indeed transpired.

Charrington went on to quote Stanley Salvidge, Tory politician and political fixer for the Conservatives in Liverpool, who in 1914 had written that the city that holds the cup final in 1915 will be carrying a mark of shame. This further condemnation did not stop Everton putting Goodison Park forward as a venue if the final went to a replay, an offer the FA accepted. Charrington also suggested that the guest of honour awarding the trophy to the winner should be Kaiser Wilhelm II. The FA declined that suggestion and in the end the Earl of Derby presented the trophy and medals on the day.

The Easter weekend brought further problems. Good Friday at first glance passed off without controversy. On Saturday the match between Middlesbrough and league title contender Oldham Athletic caused more bad publicity. After 55 minutes with Middlesbrough winning 4-1, the Oldham Athletic defender, Billy Cook, was sent off but refused to leave the pitch. The referee Mr H Smith of Nottingham had to abandon the match.

On the 16th April the Football League ruled that the result would stand and Billy Cook would be banned for a year. Before that was laid to rest another rotten Easter egg came to light. Suspicions of a fixed match on Good Friday began to circulate. On the 19th April a commission of the Football League talked to Liverpool players and officials, then the next day they spoke to Manchester United players and officials. On 21st April the Liverpool Echo was reporting that a Manchester bookmaker was offering £50 for information about the fixing of a match played on Good Friday in Manchester. The only match it could be was Manchester United v Liverpool.

Many on hearing about this match, recalled the infamous Stoke v Burnley test match of 1898. In that match a draw would see Burnley promoted and Stoke remain in the First Division, and so a nil all draw was the result. The game itself was later dubbed the match without a shot! In the same Manchester Courier, the match report in 1898 made it pretty obvious that something was going on. But this time reading the match report of Manchester United v Liverpool in the same paper it was not so obvious that a fix was on.

The Manchester Courier reported that in showery weather, United had much the better of the game, with the visitors being “overplayed” their defence played well and Liverpool keeper Elisha Scott was singled out for praise. Manchester United deserved their 1-0 lead at half time. The second half was described as scrappy and a penalty awarded to United and taken by O’Connell after 10 minutes was shot yards wide. Both sides were described as shooting badly, Anderson scored a second goal for United giving them a 2-0 win.

The Liverpool Daily Post own report described a similar sounding game. Though the reporter did say that a more one sided first-half could be hard to imagine. The O’Connell penalty was described as ridiculously wide and the second United’s goal was scored through a ruck of players. The Daily Post did praise a number of Liverpool players, Elisha Scott in goal, winger Jackie Sheldon, defenders Ephraim Longworth and Don McKinlay and forwards Jimmy Nicol and Tom Miller. The Football League launched an inquiry into this match and it would rumble on for many months damaging the reputation of football all the while.

Eventually without much fanfare the 1914-15 season drew to its conclusion. Everton won the league by 1 point from Oldham Athletic, whilst Chelsea and Sheffield United contested the FA Cup final at Old Trafford. The final later became known as the Khaki Final because of the number of solders in the crowd. Wartime travel restrictions and the fact that lots of young men were in the armed forces limited the crowd to just under 49,000. Sheffield United won a one sided final 3-0.

The losing finalist Chelsea had other problems, they were also about to be relegated to the Second Division, losing out by 1 point to Manchester United. The inquiry regarding the Good Friday Manchester United v Liverpool match could potentially reverse the final league positions, but a final resolution of this inquiry, would have to wait until the end of the war.

And finally with much relief from both the Football Association and the Football League, the 1914-15 season drew to a close. The last league match was on Thursday 29th April 1915. Only 3,000 people turned up for a Humberside derby between Hull City and Grimsby Town at Anlady Road. None of the people present would imagine that it would be more than four years before they would see the next football league match.

Playing this season to a conclusion had done the reputation of organised football no good at all. The Football League could say, with some justification that they really had no choice as the clubs had contracts to honour, but this point was ignored by the public. As with many organised team sports in England, football had been born in the English Public School system. It was this decision not to cancel the 1914-15 season that lead to many of these schools dropping the playing of football from their curriculum. A sport not played by the elite could expect little regard from this same elite.

1915-16

What was the football industry to do when the nation was embarked on total war? Many players had enlisted or gone to work in munitions factories at this point. This reason apart from public pressure against it and the practical difficulties of travelling long distances on an over stretched railway system, made it impossible to even think of starting a new regular season.

The Management Committee of the Football League meeting on Saturday 2nd July 1915 at the Winter Gardens, Blackpool came to the conclusion that the war was not going to end before the scheduled start of the new season in September 1915. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was fully engaged in France at this time. The Second Battle of Ypres had ended in May with nearly 60,000 British casualties. This was followed by the Second Battle of Artois which end in June with a further 28,000 British casualties. By September the scheduled start of the football season, the BEF was undertaking its biggest offensive of the war so far. It would become known as the Battle of Loos and it would cost a further 60,000 casualties.

The Blackpool meeting decided that in order to keep the sport alive some sort of competition would have to be organised. 40 league clubs wanted to take part in the new proposed system of three leagues organised on a geographic basis. It was also decided they would have a principal league followed by a secondary league. The clubs would only pay players expenses and the clubs would also keep the players registrations. They also decided that all matches would be played on Saturdays or holidays. As it turned out all matches took place on Saturday, except for Boxing Day, Good Friday, Easter Monday and the Tuesday after Easter.

The major problem of who would be relegated to the Second Division was kicked into the long grass. There was an enquiry still running, into the now infamous Good Friday match so no decision could be made anyway. What the Football League did decide was who was in and out of the league when peace finally came. Leicester Fosse were re-elected, but Glossop were out. Stoke replaced them whilst South Shields, Chesterfield Town, Darlington and Coventry City missed out.

A second meeting of the Management Committee took place on the 2nd August 1915 at Bramall Lane, Sheffield. It was at this meeting chaired by ‘Honest’ John McKenna, the Liverpool chairman and president of the Football League, that details for the new season were ironed out. These three new sections would be centred on Lancashire, the Midlands and London.

The Lancashire Section centred on the railway systems of the London & North West Railway Company and the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Company consisted of First Division clubs Manchester City, Manchester United, Everton, Liverpool, Burnley, Oldham Athletic and Bolton Wanderers. Blackpool, Bury, Preston North End and Stockport County came from the Second Division. Three non-league clubs Rochdale, Southport Central, and Football League elect club Stoke made the numbers up to 14 clubs.

The Midland Section made up of 14 clubs consisted of Bradford City, Bradford Park Avenue, Sheffield United, The Wednesday, Derby County and Notts County from the First Division. Barnsley, Grimsby Town, Hull City, Lincoln City, Leeds City, Huddersfield Town, Nottingham Forest and Leicester Fosse came from the Second Division. These clubs were served by the Great Central Railway Company and the Midland Railway Company. Lancashire Combination club Tranmere Rovers attempted to join the Midland Section as Birkenhead was part of the Great Western Railway network with good links to Birmingham, but they were refused.

The London clubs broke away from the Football League jurisdiction and using the good officers of the London FA and the Southern League organised their own league, the London Combination. The wartime league consisted of Arsenal, Chelsea, Clapton Orient, Fulham and Tottenham Hotspur from the Football League. The rest of the league was made up of Southern League clubs Brentford, Croydon Common, Crystal Palace, Millwall, Queens Park Rangers, Watford and West Ham United. This breaking away of the London clubs and the alliance of the London FA and the Southern League was and would be of grave concern to the Football League when peace returned.

Because White Hart Lane had been taken over by the Ministry of Munitions, Spurs had to play all their home games at Highbury for the duration of the war. Of the rest of the Football League clubs Aston Villa, Birmingham, Blackburn Rovers, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers decided to play in local leagues. Bristol City isolated out in the south west were left in the cold.

All three leagues got underway on Saturday 4th September 1915 without mishap. Match admission was set at 6d and the first few weeks passed without incident. The Lancashire and Midland sections under the control of the Football League were deemed a success as was the start of the London Combination.

Apart from two abandoned games, from which the results were allowed to stand, plus Hull City and Croydon Common turning up men short for fixtures, 1915 drew to a successful end. Bristol City who had been stuck playing games against local sides, finally had a league to play in with the forming of the South West Combination in January 1916. Joining Bristol City were Southern League clubs Cardiff City, Newport County, Portsmouth, Swindon Town, Southampton and city rivals Bristol Rovers. All these clubs were served by the Great Western Railway Company and the London & South Western Railway Company.

The London Combination came to an end in January 1916 and it was replaced with a secondary league of 14 clubs. Southern League clubs Luton Town and Reading joined the new London league. Both the Lancashire and Midland leagues came to an end and they too were replaced by secondary leagues. Stoke and Rochdale switched from the Lancashire to Midland sections along with new members Chesterfield Town and Rotherham County.

The running sore of the 1915 Good Friday match between Manchester United and Liverpool came to a conclusion, well as far as the Football League were concerned. In December 1915 the Football League found seven men guilty of match fixing. Four Liverpool players, Jackie Sheldon, Bob Pursell, Tom Fairfoul and Tom Miller and three Manchester United players, Enoch West, Sandy Turnbull and Arthur Whalley. Two of these Liverpool players had be singled out for praise in the match report by the Liverpool Daily Post at the time. An eighth player a L. Cook from Chester was also found guilty, but his part in it all remains a mystery. Jackie Sheldon, in a letter to the Athletic News, written from the Western Front in France, protested his innocence. Later in 1917 he admitted his guilt. All the players were banned for life, this was later set aside in regard for their war service.

Where attendances were published the average attendance for wartime matches was 5,615 with a total of well over 1,000,000 watching all four leagues. The one unfortunate event of the season was the death of former Arsenal and England player Bob Benson who collapsed during the second half of a home match against Reading on the 19th February 1916. After working a long 17 hour evening and night shift at the Woolwich Arsenal, Bob had turned up to watch a match at Highbury. When an Arsenal player failed to turn up, a tired and unfit Bob took his place. He became ill and had to leave the field before the end and he later died in the Arsenal dressing room from a burst blood vessel from a long standing medical condition.

1916-17

When the Football League Management Committee held its meeting at the Grand Hotel, Manchester on Monday the 17th July 1916 it was obvious that the war would be entering its third uninterrupted year. The massive Battle of the Somme was underway in France, a battle that would drag on for 4 months cost 420,000 British casualties.

For the 1916-17 season it was a case of same again. First Division Blackburn Rovers and Central League Port Vale joined the Lancashire Section. Southern League clubs Luton Town, Reading and Southampton joined the London Combination and Birmingham joined the Midland Section. There would be no South West League this season leaving Bristol City shut out again.

The new season followed the same course as the previous season. The only real problem being Reading resigning in October from the London Combination. Portsmouth took their place and completed their fixtures. Lancashire and Midland sections had secondary leagues as the previous year whilst the London Combination played each other 4 times so no secondary league was necessary. Where attendances were published, the season’s average attendance was 4,707. The overall total was well over 3,000,000. This number watching football during a world war might seems a lot, but the last peace time season attracted nearly 12,500,000 spectators, and in the first year of the war 1914-15 7,500,000 people attended.

1917-18

The end of season meeting of the Football League on Monday the 17th July 1917 at the Grand Hotel, Manchester, came to the same conclusion as it had the year before, the war showed no signs of coming to an end any time soon. Russia had become a republic and America had joined the war. Before the month was out the BEF took part in the Third Battle of Ypres, later to be known as the Battle of Passchendaele. The battle would come to an end after three months and cost 440,000 British casualties.

It was a case of same again for the 1917-18 season. The London Combination decided to slim down to just London based clubs meaning Watford, Luton Town, Southampton and Portsmouth were left out. On the 1st October 1917 football admission prices went up from 6d to 9d because of the extension of the Amusement and Entertainment Tax on to football. Despite the new tax, attendances where published, gave this season an average attendance of 5,616. The overall total was well over 3,000,000.

The only new feature of the 1917-18 season was a two leg play off final between the winners of the Lancashire and Midland sections. The first leg saw Midland champions Leeds City beat Lancashire champions Stoke 2-0 in front of 15,000 at Elland Road. The second leg at the Victoria Ground saw Stoke win 1-0, but lose 1-2 on aggregate. This was a notable achievement for the Leeds City manager Herbert Chapman. His had previously managed Northampton Town when they won the Southern League.

1918-19

The fourth wartime Football League Management Committee meeting took place on the Monday the 15th July at the Grand Hotel in Manchester. As with the other meetings the war did not look like it was about to end. Actually the war looked like it might end with victory for Germany. Russia had dissolved into civil war and the Americans were finally arriving in Europe in numbers. On the same day as this meeting, Germany opened their fourth offensive of the summer, an offensive that would later be known as the Second Battle of the Marne. These 1918 German offensives cost 420,000 British casualties.

In organisational terms the new season was more of the same please. The only change in clubs was Southern League club Coventry City joined the Midland Section. Southport Central asked the Football League to change their name to Southport Vulcan, the clubs new sponsors. This was against Football League rules, but they allowed it because of the special circumstances of wartime football. The season started on the 7th September 1918 and things carried on much as the previous season.

Before September was over Germany was looking for a way out of the war, but of course this was not known by the general British public, so when peace came on Monday 11th November 1918 it came as something of a surprise.

On Friday the 29th November 1918 a Special General Meeting was called at Manchester. It was obvious that though peace had arrived the Football League could not restart new regular season. Many clubs did not have their players available or their regular supporters. Many young men were still in France or at sea and it would be months before they would be returning home. They decided to carry on as planned with the scheduled fixture list.

The Football Association (FA) though did have an opportunity stage a truncated FA Cup competition for 1918-19. The idea was floated of having a first round consisting of Football League clubs and Southern League clubs, plus 4 non-league clubs. The FA decided that it would be unfair to the rest of its members and it was dropped.

January 1919 brought new wartime leagues, as clubs prepared for a new regular 1919-20 season. The north east clubs Newcastle United, Sunderland and Middlesbrough formed a Northern Victory League inviting Darlington Forge Albion, Durham City, Hartlepools United, Scotswood and South Shields to take part. In April 1919 Midland clubs Aston Villa, Derby County, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers set up a smaller scale victory league amongst themselves.

The FA was also able to bring back international matches. Two Victory Home International matches were set up for England and Scotland to play home and away in April and May 1919. In the first England drew 2-2 with Scotland at Goodison Park in front of 45,000. Hampden Park had 80,000 watching Scotland lose 3-4 to England in the return. Another Victory Home International between England and Wales was set up for October 1919. England won that one 2-0 at the Victoria Ground, Stoke in front of 16,000. This match brought us into the new 1919-20 season and the problem of Chelsea.

1919-20

On the surface it would seem simple enough to set up a new regular season, but things had changed. The Southern League clubs wanted to join the league and why not, they had played successfully against Football League clubs during the war. The Southern League proposed either an expanded Second Division of 40 clubs, or a new Third Division. Many felt accepting 20 new clubs based predominantly in the south of England would affect the balance of power within the league itself. Northern and midland clubs had dominated league football from its inception and this would tip the balance more in favour of the southern clubs.

Rejecting out of hand the Southern League did highlight a bigger fear for the Football League, a London breakaway. The London Combination had successfully run itself during the war and the league clubs based in the south could leave the Football League, join the Southern League forming a strong rival to it. What didn’t help was that at the end of the last regular season two London clubs, Chelsea and Tottenham Hotspur were in the relegation places. If they went down this would mean there would be no London based clubs in the First Division for the new season.

An extra complication was the fixed match between Manchester United and Liverpool on Good Friday 1915. The fallout from this 2-0 win for Manchester United and the 2 points awarded pushed Chelsea into the relegation zone. Because it was the players involved who were held responsible, Manchester United were judged to be innocent in all of this as were Chelsea and it seemed unfair to relegate them. In fairness you could not stop either Derby County or Preston North End from being promoted. So what was decided was that both divisions would be expanded from 20 to 22 clubs.

The last two previous league expansions in 1898 and 1905, had seen the supposed relegated clubs stay up, but that would not happen this time. Behind the scenes Arsenal chairman Sir Henry Norris, Conservative MP for Fulham East, was influencing other members of the Football League to a different solution. Norris had his own problems to solve as well. He had been the driving force behind moving Woolwich Arsenal to north London, dropping the Woolwich name and basing them at Highbury. He had ploughed £125,000 into Arsenal since 1910 and they were still £60,000 in debt.

The Football League had lost a lot of good will by continuing the 1914-15 season and they needed friends in high places and Norris, being a member of the House of Commons was the league’s man in Parliament. Norris wanted the decision as to who makes up the extra places in the First Division to go to a vote. In the ballot were the two relegated clubs Chelsea and Tottenham Hotspur and from the Second Division were Arsenal, Barnsley, Birmingham, Hull City, Nottingham Forest and Wolverhampton Wanderers.

The Football League meeting at the Grand Hotel, Manchester on Monday the 10th March 1919 was where these problems would be thrashed out. Chelsea, the innocent party, were elected without a vote. Despite the other clubs in the ballot it was the two other London clubs Tottenham Hotspur and Arsenal who were the leading candidates. Arsenal had been had been in the league for 22 seasons whilst Tottenham Hotspur have only been in the league for seven seasons though they had won the FA Cup in 1901 before they joined the league. Comparing attendances 253,000 had watched Tottenham Hotspur, whilst 252,067 had watched Arsenal in 1914-15.

There didn’t seem to be much to choose between them, so when the Football League votes came in it was something of a surprise. Arsenal had won 18 votes to 8. Spurs were dumfounded, though the press at the time had got completely behind Arsenal, it was a surprise to the football public. Tottenham Hotspur had the advantage of being incumbents so to speak and most believed they should be given the last place, but they had not reckoned on the persuasive ways of Sir Henry Norris. His Arsenal became a First Division club without a ball being kicked.

The four clubs elected to the Second Division of the Football League were Coventry City, Rotherham County, South Shields and another London club West Ham United. Port Vale missed out by one vote, but they took the place of Leeds City who were expelled from the league for financial irregularities on the 19th October 1919. Yet another football scandal to damage the repetition of the sport, so battered over the last five years.

Finally the 1919-20 season kicked off on Saturday 30th August 1919, 1,584 days after the last league match. In between 867,829 British people had died, another 1,675,000 had been injured and the world had changed forever.